In the weeks before she died, Caroline Flack had met with documentary makers in the hope of reclaiming a story she had felt on the periphery of, despite it being hers.

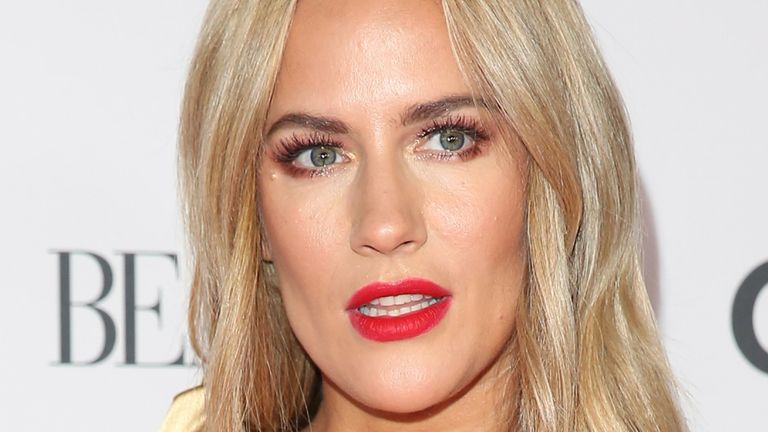

A successful presenter, Flack was a former X Factor and Xtra Factor host, a Strictly Come Dancing winner and the face of Love Island, one of the biggest TV phenomena of recent years.

But in the early hours of 12 December 2019, she was arrested on suspicion of assaulting her boyfriend, Lewis Burton, and subsequently charged.

What happened that night set off a chain of events that would lead to her taking her own life just two months later.

Facing a trial, as is usual when legal proceedings are active, Flack had been warned not to speak out about the alleged assault. Instead, she had to watch as headlines and comments on social media mounted, the job she loved gone.

This was a high-profile celebrity charged with a crime, which would always be reported. But the amount and prominence of the coverage – what must have felt like punishment before having a chance to prove her innocence – had a crushing effect.

Columnists gave their opinions, and on social media she was labelled by many as an “abuser”. Following her death, there was a rush to place blame – the police, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the press, social media – and calls to “be kind”, words she had used herself in the past.

At the star’s inquest, questions were raised by her family as to the seriousness of the alleged assault and whether the charge was necessary. Despite making the 999 call, Burton had said he did not want to go ahead with it, but the police and the CPS defended their decisions.

Before Flack’s death, she had hoped the charges would be dropped, and the thought of a documentary to air later down the line would put her story out there. But in the end, it wasn’t to be.

Her mother Christine and twin sister Jody are now hoping to honour her wish in Caroline Flack: Her Life And Death, a new documentary about Carrie, the bright and funny but incredibly complex woman behind the media persona, which explores her depression and the pressures that fame, social media and the press had on her throughout her life.

“Quite close to the end, she had actually asked us to help her tell her story,” says Jody, speaking to Sky News and other journalists ahead of the programme’s release. “She said ‘We’re going to make this film, you’re all going to be in it’. And she was excited about being able to do it. So we remembered that.”

As a private family there were initial hesitations, but in the end it felt like “something we just had to do”, she says.

“There was so much negative press around her at the end and she wasn’t a negative person,” says Christine. “She was a fun-loving person but she had this other side that she suffered with, depression and down times and just bad times.”

Her daughter “wasn’t an awful girl”, she says. “She wasn’t horrible – she wasn’t perfect, but… she didn’t have any bad in her.”

Christine and Jody met with director Charlie Russell and executive producer Dov Freedman, who had spoken to Flack in the weeks before her death.

“It was clear she had a story she wanted to tell,” Russell tells Sky News in a separate interview. In a “small way”, she has still been able to, says Freedman. “There’s elements in this film that I hope Caroline would have liked and be pleased with.”

Flack was a woman who, on the face of it, had everything: successful career, glamorous lifestyle, a loving family. She wore her heart on her Instagram, sharing what appeared to be every aspect of a life lived to the full, from relationships to parties to behind-the-scenes filming and messing about with friends.

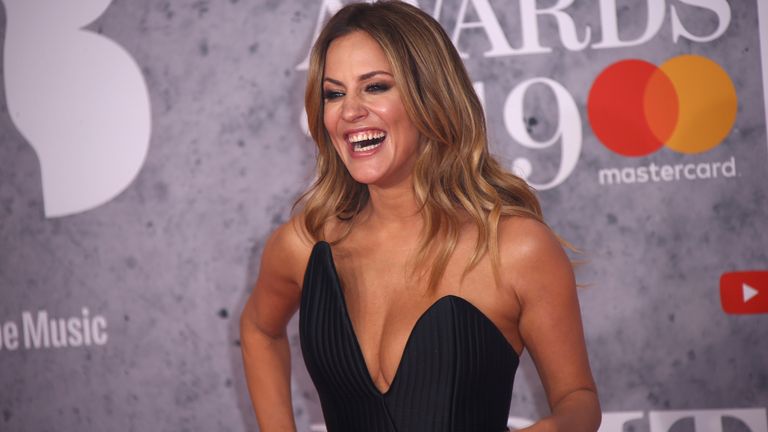

But behind the grin and infectious laugh that made her famous was a woman who had always struggled, with everything from teenage break-ups to negative press and trolling on social media. That only increased the more famous she became.

She had taken tablets and “ended up in an A&E situation a lot of times”, which her family are talking about now for the first time.

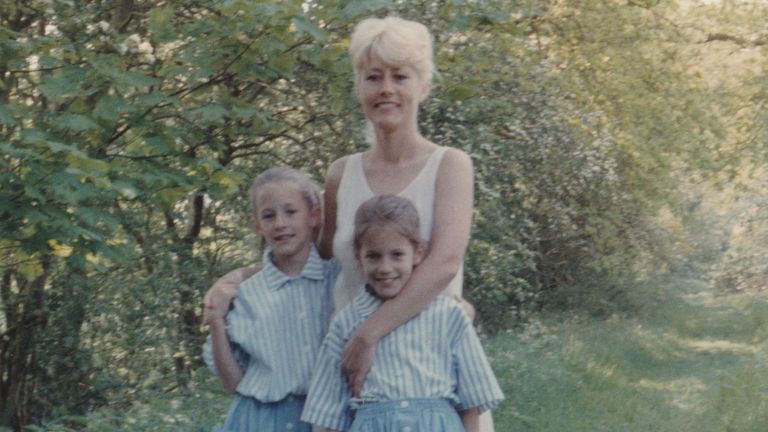

From childhood, Flack “was either very high or she was very down, you couldn’t stop her crying”, says Christine in the documentary. After her first break-up “she struggled emotionally, she was very depressed”, says Jody. “And that pattern carried on forever. She really did find heartbreak impossible.”

Suicide was a worry “for a long time”, she says. “I’d prepared that it could happen.”

As well as interviews with Christine and Jody, friends including Olly Murs and Dermot O’Leary also pay tribute to Flack. The programme features previously unseen home videos and photographs, showing a young girl with her whole life ahead of her.

“I probably wouldn’t have looked at them yet [if not for making the documentary],” Christine tells the panel Q&A. “There’s lots of things we can’t do yet. My oldest daughter still hasn’t even looked at the Strictly film, she can’t bring herself to look at things yet. But I think because we were doing this, we were looking at things again and remembering, funny things that she’d written and… yeah, that was really nice.”

Flack was by no means a reluctant celebrity. She worked very hard but also enjoyed being famous, her family and friends say in the programme.

But she wasn’t “emotionally wired” to deal with the negative aspects when things went wrong, says one producer, and became “addicted to affirmation”, O’Leary believes. She could not keep herself from reading news stories and checking her social media feeds.

“When I was young, if you were bullied at school you could get away from it,” says Christine. “You can’t get away from it now because it follows you home, it follows you on your phone.

“Carrie was the worst one, she would look at her phone all the time. It took her over, what was being said on there. There could be 30 nice things said, one bad thing said, and that was it.”

She believes social media companies should take action over abuse online. “They are making so much money, it is not that there’s a lack of money of profits will suffer,” she said. “Someone’s got to take a responsibility somewhere for it.”

In the weeks following Flack’s arrest, a photo of blood-stained sheets from the night of the incident was printed by some newspapers. At her first appearance in court, when she pleaded not guilty, the prosecutor detailed how emergency services arrived at the scene to find both Flack and Burton “covered in blood, and in fact one of the police officers likened the scene to a horror movie”.

Without details of whose blood it was, when details of the court hearing were reported, many assumed that, as the “victim”, it must have been Burton’s.

In a statement Flack wrote but never published before she died, later released by her family, she said: “The blood that someone SOLD to a newspaper was MY blood and that was something very sad and very personal.” In the trailer for the documentary, footage that she had started to film herself shows the presenter crying, and saying: “The only person I ever hurt is myself.”

She had received bad press before and got over it, says Christine. “But this time she couldn’t see a way out.” The case “triggered everything in her life that she finds difficult,” says Jody.

Speaking about the press coverage at the Q&A, Christine questions “why it should be front page… the awful things that are happening in this world” and later says she was “followed across London” by some journalists “after I’d cleaned up the blood in Carrie’s flat” following her arrest. “That’s how bad they were.”

The documentary has evolved into something more than just sharing Flack’s story, with a focus very much on mental health. It is an issue Flack was desperate to keep hidden – visiting “different doctors all the time so no one could find out… because she was so fearful of anybody knowing anything and printing it” – but that her family have decided is important to share.

“I think if she wasn’t in the public eye, she might have opened up a bit more,” says Jody. “She was always so scared that anything would not be taken well or would be ridiculed.” She says she used to “often” tell her sister that she should do a different job to protect her mental health.

“But she was doing what she did best and she loved it. It was completely the wrong advice because she absolutely thrived on what she did and she would never have stopped doing it because that’s what she wanted to do… life would have been a lot easier if she’d done a different job. But that wasn’t… Carrie was never going to have an easy life. She wasn’t built to do that.”

Jody hopes the programme will make “a big impact on other people” and “reduce some shame – there is such a lot of shame involved in all this, which there didn’t have to be”.

“I think it’s very hard to comprehend if you’ve not suffered from proper depression and mental health problems in the way that she did,” says Russell. “I think it’s quite hard for us all still to imagine what that is like and what effect that has on your life.

“All of her family and friends talked about the fact that when she was up and good, she was really happy and joyous and loving life, but that could change quite quickly and she could be so down and so low. I think it’s hard for us to comprehend what that actually feels like and therefore, what a massive challenge is to try and share that with other people.”

Jody and Christine, he says, had “grappled with how she would feel about” sharing it. “I think ultimately they feel like there’s a kind of greater good in making this film now that can come out of it.”

Christine hopes the documentary will help people better understand her daughter.

“The things that were written about her and said about her being an abuser – because they’re the things that stuck and they’re the things that got repeated – I wanted to show, you know, she was just an ordinary girl. That wasn’t her. What was shown at the end wasn’t her.

“As I said before, she wasn’t perfect, but that wasn’t her… I wanted the memory to be of this positive, nice person. My daughter and [Jody’s] sister, she never changed, she was good to us, and she was lovely.”

“I think we’re all complicit in the way that Caroline and others are treated by the media… that combination of social media and press headlines and just gossip,” says Russell. “It even crosses over to the news today, discussions about people in the public eye, essentially discussions about their private lives. And we are all guilty of reading that stuff, watching that stuff, being intrigued by it… people in the public eye pay a price for having that level of scrutiny.”

“What we hope people take from it is – and this doesn’t apply only to people in the public eye – you don’t know what’s going on behind closed doors,” says Freedman. “Maybe just think about things that you say to people and how it might affect them a little bit more.”

While Flack never got to tell her story in her own words, Christine says she thinks she would have been pleased with the outcome.

“I’m really sad that I’m sitting here talking about this film and she’s not sitting here talking about the film that they were going to make,” she says. “Because that would have been the best thing.”

Caroline Flack: Her Life And Death airs at 9pm on Wednesday 17 March on Channel 4. Anyone feeling emotionally distressed or suicidal can call Samaritans for help on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org in the UK. In the US, call the Samaritans branch in your area or 1 (800) 273-TALK