It opens with the crescendo of a dark, sweaty gig, a mixture of throaty vocals and feedback and cymbals clashing, before cutting to the almost-silence of the morning.

From the offset, Sound Of Metal makes you incredibly aware of what you are hearing as well as seeing on screen; not just the conversations, but the background haze we hear every day but pay little attention to.

When that is taken away, you feel it.

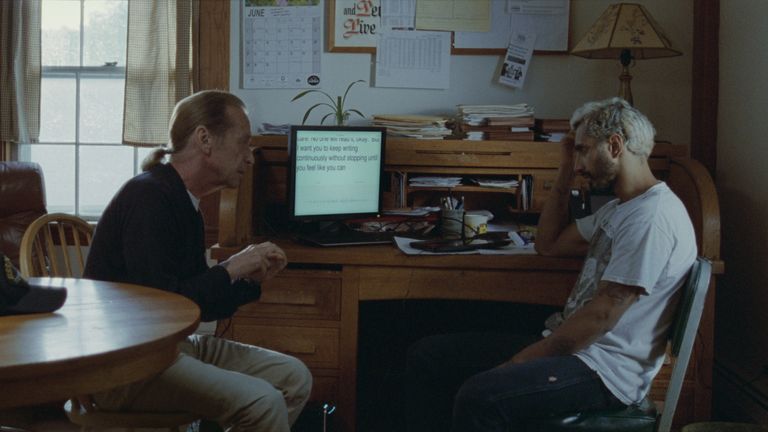

There has been a lot of well-deserved buzz around this film – six Oscar nominations, four BAFTA nods, and several critics’ prizes already won for stars Riz Ahmed and Paul Raci – yet it is perhaps not your typical Hollywood awards season fare. Ahmed stars as Ruben, a punk-metal drummer and former drug user who very abruptly loses his hearing; Raci as Joe, a deaf veteran running a home for addicts with hearing loss.

It is a film writer and director Darius Marder worked on for around 13 years to bring to the big screen and had to argue for the need for open captioning, which details every sound as well as the dialogue and cannot be removed by the viewer.

For a film about deafness, it seems an odd thing to have to convince executives of the merits of, but tells you everything you need to know about Hollywood and accessibility for people who cannot hear. It’s also strange as even for the hearing audience, it only serves to heighten the experience.

For Marder, whose grandmother, Dorothy, became deaf later in life, it was non-negotiable.

“This was not a popular idea,” he says, speaking on a Zoom call. “Many and most people told me I wouldn’t be able to sell the movie. ‘You can’t do that, no one will watch it, it will ruin the movie’.

“This film is dedicated to my grandmother. She was stuck between hearing and deaf culture, without any access to either, and it really unravelled her.

“One of the greatest losses was cinema for her because there’s no access to cinema. In those days, there was no streaming with captions, with closed captions, but certainly not any open captions on movies in theatres. She petitioned for the rest of her life for open captions. I knew when I made this film that I had to open caption it.”

Arts charity Stagetext, which provides captioning and live subtitling in theatres and cultural venues, says it saw an increase in demand for live captioned performances online following the first UK lockdown in March 2020. Almost one in five UK adults (18%) are deaf or have hearing loss, it says, but fewer than 1% are fluent in sign language.

In Sound Of Metal, as Ruben has to learn a life of sign language and lip-reading, the captions at first disappear from some scenes; as he gets used to an ableist world, so too does the viewer.

“You might, as a hearing person, feel like, ‘what the hell are those doing there? I don’t want to see those’, or, ‘I don’t usually see those, can’t we turn those off?'” says Marder. “[But] you’re going to get used to [it] and it might actually elevate the movie for you, even as a hearing person. It certainly does as a deaf or hard of hearing person.

“When those captions are taken away, you’re suddenly… as most hearing people, like, ‘wait a second – what?’ Because we’re not used to not having access to everything. We never have to contend with that. But Ruben does. In many ways, the film is from an able-bodied perspective. It’s from that perspective that’s used to it and has to then contend with actually [becoming] a minority.”

Raci, whose parents were both deaf, is also someone with personal experience of the deaf community. American Sign Language (ASL) is his first language, English his second.

“My father was deafened at the age of six months from spinal meningitis, so he never knew sound at all,” he says, speaking to Sky News on a separate call. “My mother was deafened at the age of five years old, so she did remember sound. She spoke and read lips, a lot like Joe does in the movie.

“I was kind of a conduit to the hearing world [for my parents]. I’d be in the middle of negotiations for a car or maybe a mortgage, on the phone with the gas company – ‘please don’t turn the lights off’, that kind of thing. I would interpret the television to my father.

“When The Beatles came out, my mother bought me my first concert ticket. She took me to a movie when I was nine years old; we saw Love Me Tender, starring Elvis Presley and Richard Egan, and I’m sitting there interpreting the whole script to my mother. So it’s a little bit of a different age, children of deaf adults, CODAs, have a little bit of a different life now, but I was in the middle of a lot of situations as a boy that were unusual. But, as I look back, a true blessing.”

Marder says he refused to cast anyone “outside of deaf culture” for the role of Joe, and turned down “offers to meet with huge actors… who might have helped finance” the film. Not only can Raci sign, but he is also a Vietnam veteran and, as the frontman of an ASL Black Sabbath tribute band, Hands Of Doom, he has the musical connections, too.

“I wanted it to be authentic and I wanted it to be respectful to the deaf community,” says Marder. “I met with wonderful deaf people, but Joe as a character is actually from hearing culture, he’s late-deafened.” Raci had “deep connections to this character in myriad ways”, he says.

Both Marder and Raci are quick to praise Ahmed, who learned ASL and how to play the drums for the role, and wore hearing blockers emitting white noise to authentically portray his character’s hearing loss.

“I really was amazed by his dedication, how he immersed himself in the sign language, the respect that he showed the culture and everybody that he met on the set,” says Raci.

“He was willing to do something that I think even goes beyond the seven months of learning drums and learning ASL,” says Marder. “The real journey here was actually losing control… [the hearing blockers] didn’t allow him to hear his own voice. So he was out of control, and not just while we were shooting, he was out of control in between shots. If he wanted to talk to me, we would have to write something down.”

The film deals with Ruben’s desperation to return to normal, which he hopes he can achieve through cochlear implants. What Sound Of Metal does not do is present this as necessarily a happy ending; deafness is not a problem that needs to be solved. As Joe tells Ruben in in one emotional scene: “Everybody here shares in the belief that being deaf is not a handicap. Not something to fix.”

“They used to call deaf people hearing impaired,” says Raci. “Right there, ‘I’m the one who has the impairment, not you’.

“When I moved out to Los Angeles in the 1990s, something like that, I started meeting deaf actors who had an opposite approach to that, who said, ‘I’m perfect, I’m whole, I’m complete just as I am’. How’s that for a novel concept of self-worth? And most of the deaf people that I know, especially deaf actors, do have that philosophy.

“That’s not to say that they’re against cochlear implants. It’s a personal decision… Although the deaf community promotes, I think, whatever is good for you and your journey, there are deaf people who have the philosophy of, ‘Don’t touch what God has done here. Everything is perfect, just as I am. If you want to learn my language and speak to me, we’ll be on the same level’. Most of the deaf people I know are proud to be deaf, and whole and complete.”

The theme of returning to “normality” resonates after a year in which the world has been trying to do just that during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, though, we’re looking to the “new normal”.

“It never really will be normal like we knew before again, will it?” says Raci. “As it is for Ruben, it just never will be again. And life does go on.

“I guess it says something about the human spirit… you throw all these obstacles in front of people, especially a lot of the deaf people that I’ve known in my life, you throw an obstacle in front of them and they brush it away and just keep on moving. And that’s the thing that Ruben has to do, he’s just got to keep on moving ahead. You’re still breathing, so you’ve got to keep living. So that’s an interesting parallel that’s happening with all of us coming out of this thing and thinking it’s going to be normal again. And we don’t know.”

In another year, without the heightened awareness about representation on screen that we have seen in the last few years, without the pandemic and the high-profile film releases that have been pushed back, Sound Of Metal might have easily, and wrongly, been overlooked come awards season. While many ceremonies in recent years have been fairly predictable, this year, more than ever, it feels like Hollywood just might finally be starting to catch up with the real world.

“But that struggle is still going on right now because Sound Of Metal is one,” says Raci. “One movie. Where are the rest of the portrayals of disenfranchised communities, if you will? The deaf and disabled, people that use wheelchairs? [Sound Of Metal] is opening it up, just a little bit, I think that it’ll start the conversation. But is there more work to be done by Hollywood? Yes. I think Hollywood knows that. It’s just going to take some peaking of awareness and expansion of awareness so people know that there’s other actors out there, there’s other stories out there to tell.”

:: Subscribe to the Backstage podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

What deaf viewers have enjoyed about the film, says Raci, is that the deaf characters portrayed on screen are not just bit-parts.

“What they have told me is that they were pleasantly surprised to see deaf people portrayed as addicts in a sober house, rather than the comic relief for one line or an incidental character,” he says. The next step is films with characters who “just happen to be deaf”, he says. “A deaf lawyer – that happens, you know. An accountant, or a bad guy! How about that? They’re just like everybody else.”

Sound of Metal is a film about identity, says Marder, raising the question of how much our ability to hear – and by extension, to see, or walk – is a part of that.

“It’s about what we are when you strip away some of those aspects of our identity. We often do look at people and say, that person’s deaf, but we don’t look further. Deafness, deaf culture is certainly not a monolith; it’s so many things and of course, that’s obvious. But yet, how curious are we? How often do we look? How often do we engage?

“So the film is so much about identity. What are we when you remove those aspects of our identity? Whether it be, I’m a drummer or I’m an orphan or I’m a foster child or I’m in a relationship or, you know, I’m an alcoholic or I’m an addict; all of those things, what happens when you strip them away? What are we? And is it enough? So I think that’s very important, that we start to kind of look past ourselves and look a little deeper into the nuance of who we are as humans.”

Both Raci and Marder say they hope the film will make people think a little deeper.

“It asks you to feel a lot,” says Marder. “It asks you to move through your own discomfort at times and to kind of go through this ring of fire with Ruben. I think what is possible when you go through that is that you might actually find yourself open to a bit of transcendence, that is something physical and emotional rather than just, ‘that’s interesting’. So I really hope that people feel something in this.”

Raci says he hopes that on a simple level, the film will make people realise that hearing is not something to be taken for granted.

“I know a lot of musicians, friends of mine – drummers, guitarists – who have not taken care of their hearing, and it’s precious,” he says.

“Protect your ears, you know. But that’s in a practical sense… the other thing is just to know that there are other cultures out there, there are other lifestyles that you have no idea about – and this is just one example of them.”

Watch Sound Of Metal on Amazon Prime Video from 12 April and in cinemas from 17 May