The theme of childhood nostalgia in South Asian fiction is packed with a lot of intensity and nuance. Childhood is never just about blissful days of yore. Deep down, childhood comes with its own share of despair, disappointments, and hiccups. As we grow older, we become more cognizant of the problematic aspects of our childhood that our young minds might have been unaware of. South Asian authors are impeccably depicting childhood in all its messy glory by shedding light on all the dire social issues that deserve our attention.

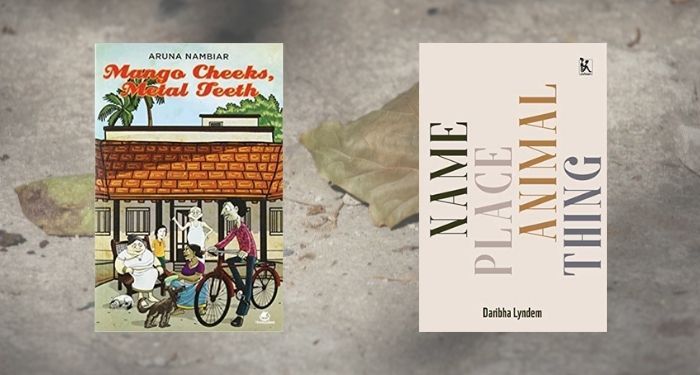

Set in the Kerala of 1980s, Aruna Nambiar’s hilarious novel Mango Cheeks, Metal Teeth is partly a coming-of-age story and partly a social satire. Geetha, a young 11ish-year-old, is really psyched about her annual family vacation to Kerala at her grandparents’ house. Geetha absolutely adores joining her cousins on trips to the beach and visiting the local market to buy bangles, kites, and other knick-knacks associated with a typical Indian childhood. She cannot wait to spend evenings with her grandfather who insists that his ridiculous ghost stories are true. An entire summer spent partaking in marathon card games and boys-versus-girls battles with brooms made from coconut fiber do sound utopian. However, amidst the trouble-free days of childhood, class consciousness, the dowry system, and social hierarchy rear their ugly heads.

Through Geetha’s eyes, we see a faulty social structure where the rich still behave like they own the poor. We meet Koovait Kannan, a former domestic help at Geetha’s grandparents’ house, who has suddenly risen in ranks, courtesy of the economic opportunities offered by the Gulf. Kannan’s daughter Bindu’s wedding has been arranged with Venu, Ration Raman’s son. This arrangement has been made for the sake of maintaining the nouveau riche status of both parties involved. This is a child’s first interaction with how marriages are still thought of as transactions. Love doesn’t come into the picture as in a capitalistic society material comforts rule the day. Ration Raman’s income comes from unlawful sources but money can blindfold the law. The desire for social mobility often pushes the characters into moral ambiguity. The wedding of Bindu and Venu brings to the fore the system of dowry by which the bride’s side is compelled to abide. The bride’s family has to offer money or its equivalent to the groom’s family, bolstering a system where women are objects to be exchanged in financial deals. Women are commodified and children are coming of age in a structure that still deems women as subhumans. The book also features the divide between the masters and the servants. The power of the rich over the poor and the sense of entitlement the former class feels over the latter are palpable throughout this novel.

Daribha Lyndem’s Name Place Animal Thing chronicles the story of a girl referred to as D and her Khasi community of India, from childhood to adulthood. Through her changing perspectives on identity, communal differences, and how the self stands in relation to the other, readers are given a glimpse into a politically and racially charged Shillong (a city in India). In this collection of inter-connected short stories, each chapter deals with a specific character through whom a certain aspect of Shillong is revealed.

Lyndem touches upon the many manifestations of racism existing within the Khasi sociopolitical ecosystem. Her Nepali neighbor, hailing from a low socio-economic background, is compelled to leave the town. One of his sons is mauled by a dog and D is left wondering why nobody comes to his rescue. There is a chapter dedicated to a Chinese restaurant owner named Tommy through whom Lyndem has talked about the insurgency movement in the state in the 1980s and 1990s. Tommy’s forefathers have moved to Kolkata more than a couple of centuries back. Now Tommy has to pack up his business and move back to Kolkata as the living situation in Shillong isn’t ideal for people like him anymore.

D is a child when the insurgency movement hits the state, so her memories of it are associated with bandhs, having to miss school, and getting to cycle on traffic-free roads. Lyndem has peppered blissful childhood anecdotes with instances of xenophobia, racism, sexual harassment, and loss. Childhood is a minefield. So many things can steadily decline around us without our conscious knowledge. Parents can’t do much to protect us as regardless of what our child brains think; they are not superheroes. In one well-executed scene, we learn about a senior who pinches D’s ‘bathroom parts’ without her consent. Through D, Lyndem depicts how much violence we as children witness on a daily basis. She stresses how childhood is as difficult and harrowing to navigate as adulthood. Young, impressionable minds adjust to the many manifestations of hate and it takes years to start unpacking the trauma. The narrative slips flawlessly into a child’s gaze and voice, thus making the adult reader ponder on the many complexities of childhood.

The realm of everyday intimacy is where social change truly begins. Social change isn’t an ad campaign, nor can we tweet our way to social change, contrary to what social media posts may make us believe. South Asian fiction, through the lens of childhood nostalgia, speaks of the everyday indignities we suffer at the hands of our employers, neighbors, friends, and communities. It exposes how sometimes our inflated sense of self keeps us from introspecting and thus inhibits us from changing our ways to bring about active change. The theme of childhood nostalgia also helps traverse trickier territories, pulling into focus all the oppressive ideologies we as children internalize. We grow up normalizing these principles,, as unlearning doesn’t happen without a conscious effort on our part. Contemporary South Asian fiction is urging us to reevaluate our childhood biases and take a more constructive approach to debunk them.

For more books on South Asia and what’s it like to inhabit this part of the world, please check out these spectacular reads!