Authors have the unique responsibility of building new worlds; readers have the privilege of living in those imagined worlds. In the climate fiction genre — stories that revolve around life in a changed or changing climate — the world being co-created is one that projects our current science and anxieties out into a distant world. It’s a heavy burden, but the best climate fiction books can anchor us within hope as a form of resistance, inspire new ways of adaptation, and reframe our possible futures.

Because, let us be clear: climate change is happening, but we are also at a decisive point in its progression.

Environmental issues are being decided in elections and legal precedents around the world. We are hitting record numbers when it comes to heat and other climate change effects, but as David Gelles at The New York Times noted, we are also at a remarkable inflection point: “Global carbon dioxide emissions may have peaked last year… [W]e now appear to be living through the precise moment when the emissions that are responsible for climate change are starting to fall.” NYT’s coverage continues to focus on this tipping point. Nonfiction authors like Hannah Ritchie and Zahra Biabani are building bodies of work focused on climate optimism and potential solutions to these very real problems.

There’s a very real precarity when standing on the edge of this inflection point. It can feel hopeless. But, there’s also power in getting to choose what our future looks like. What an incredible responsibility; what an incredible privilege.

Thankfully, as readers, we have help. Today’s best climate fiction authors are leading the way, and in many cases, they’re not simply guessing at what the future could hold. They’re reaching into our history to highlight the roots of our current issues, as well as solutions and community-based ideas to inspire our future. This is where to get started with today’s best cli-fi authors.

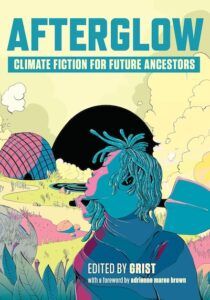

Look first to Grist, a newsroom that explores solutions at the intersection of climate and justice. Along with their excellent reported pieces, their Imagine 2200 climate fiction contest and collection Afterglow elevates new authors in the genre and celebrates stories that offer vivid, hope-filled, diverse visions of climate progress.

Tory Stephens, Grist’s climate fiction creative manager, explains why cultural and geographic diversity among climate fiction authors is so important for tackling global climate change today, noting:

“Let’s start with the fact that not every story is global, but climate change is, and the impact it has on a locale is different depending on where you live on the earth… Authors from different regions can highlight the specific environmental challenges their communities face due to climate change. This showcases the diverse impacts of a global phenomenon. They can also present solutions that are culturally specific and adapted to local conditions, offering a broader range of possibilities…

Historically, narratives around environmentalism have often been dominated by Western perspectives. Non-western authors can challenge these narratives and offer new ways of thinking about the relationship between humans and nature. They can also highlight the disproportionate impact of climate change on marginalized communities…

We need to be discussing the climate. Diversity in climate fiction does that, because it makes the genre more relatable, and thus more accessible.”

There is a wealth of places to start building your own climate fiction bookshelves and, by extension, your own broader understanding of our potential climate futures.

Stephens recommends Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doer, calling it a masterclass and “a testament to the power of storytelling to inspire and mobilize people.”

C Pam Zhang’s best-selling Land of Milk and Honey is a novel with a rich appetite that explores themes of privilege, desire, and survival, set in a dystopian future where a chef navigates a world of extreme scarcity and indulgence. In Zhang’s words, we find ourselves and the ethically difficult choices we face every day.

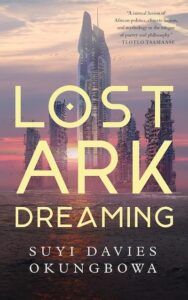

Suyi Davies Okungbowa is the author of the incredible novella Lost Ark Dreaming in which he explores themes of intergenerational justice and the long-term impacts of climate change, explaining:

One thing I learned writing Lost Ark Dreaming is that if you take a current challenge — climate and otherwise — we’re facing as a human collective, and cursorily scratch the surface, it’s hard not to unearth a variety of things that, while not direct causes themselves, are natural forebears and precursors of these things. Historical violences, malpractices, injustices, and social and infrastructural design failures, visited upon land and people, repeated over time, shuttled across generations, fed one into the other, building mountainous consequences that eventually manifest today, whether as a climate consequence or other related matters of social inadequacy.

These kinds of connections are difficult to explain in everyday words to the average person; to, say, demonstrate how a city’s present-day flooding and its colonial history are linked. But this is where fiction comes in. It opens the door to a reader to enter a reality, and then within that, pathways to other realities the reader may pay witness to. In this way, a reader may occupy the past, present and future all at the same time, making connections for themselves that the author may have only marginally alluded to. Writing fiction, and reading it, is in this way, synapse-creating work. And if there’s any matter of interest today in which we need that help making historical connections, envisioning plausible — and hopeful, just, beneficial — futures, it’s climate and the environment.

This is where fiction comes in. It opens the door to a reader to enter a reality, and then within that, pathways to other realities the reader may pay witness to.”

Enter these new realities with novels like Imbolo Mbue’s How Beautiful We Were, Analee Newitz’s The Terraformers, Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High We Go In the Dark, Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, Premee Mohamed’s The Annual Migration of Clouds, and Cherie Dimaline’s YA novels The Marrow Thieves and Hunting by Stars.

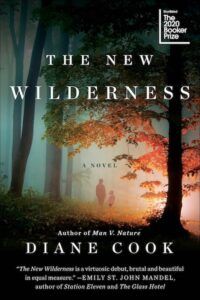

Diane Cook, author of the captivating The New Wilderness, carries this connection to our shared ecological and literary history further, reflecting on the body of work from groundbreaking climate fiction authors like Amitav Ghosh. Cook writes:

“These days, climate writers are trying to urge the population to connect to the world so they’ll want to save it. They’re trying to convince readers that what we do right now will affect our future, and that our relationship with the world around us matters. The natural world is usually thought of as ‘place’” and we often only notice its power and influence when that place is so strong that it becomes a kind of character. Literature is preoccupied by human characters and too often forgets those characters exist within an ecosystem.

What I’m so struck by in Ghosh’s work is that, even decades ago, he wrote characters who always intrinsically knew how the natural world affected them, and how it helped them and endangered them. They knew their place in the ecosystem. The natural world affected most aspects of their lives and they knew it. Their relationship with the natural world was still intact. It’s what made their story worthy of telling, and what made those books, books like The Hungry Tide riveting. It reminded me that focusing my lens on climate change didn’t just mean exploring a future we have yet to see, but I could emphasize the relationships we’ve always had with the natural world, as a way to unearth that buried connection for the reader. To repair the broken seam…

So many of us have been alienated from our natural environment–we can find that relationship again in books that center a natural world that’s not just in crisis, but one that is still inextricable from who we are.“

In a moment when we’re deciding what we want our future to look like, with two very different visions ahead, today’s climate fiction authors are showing us how lessons from our past and our context within the world can help us find the path toward a more hopeful, interconnected, inclusive, and honest future. To repair the broken seam. Let’s follow it.