Norton Juster, an architect and children’s book author best known for writing The Phantom Tollbooth, has died at age 91 at his home in Northampton, Massachusetts. His daughter Emily Juster said he had been dealing with health complications related to a stroke.

Juster was born in Brooklyn in 1929 to Samuel Juster and Minnie Silberman. Samuel Juster was a Romanian immigrant and became an architect, and Norton’s brother Howard was also an architect. Norton studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and then later city planning at the University of Liverpool. His penchant for children’s stories came out during his time in the Civil Engineer Corps of the United States Navy, which he joined in 1954.

During his ascent to Lieutenant Junior Grade, he started writing and illustrating children’s stories while stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Juster also started an exclusive membership group called the Garibaldi Society that existed solely to reject prospective members. These early days of his interest in children’s literature and meeting Jules Feiffer for the first time is outlined in The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth, which was published in 2011 for the 50 year anniversary of the book.

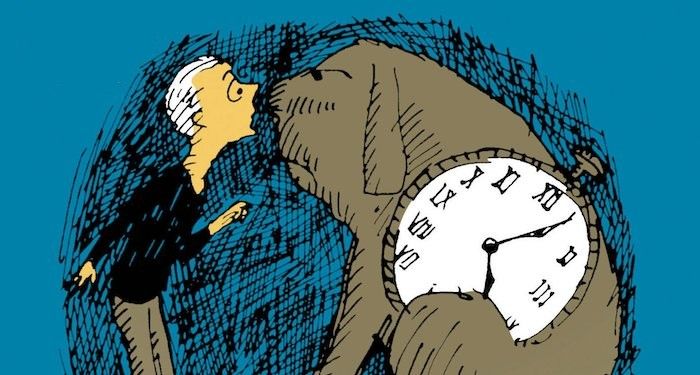

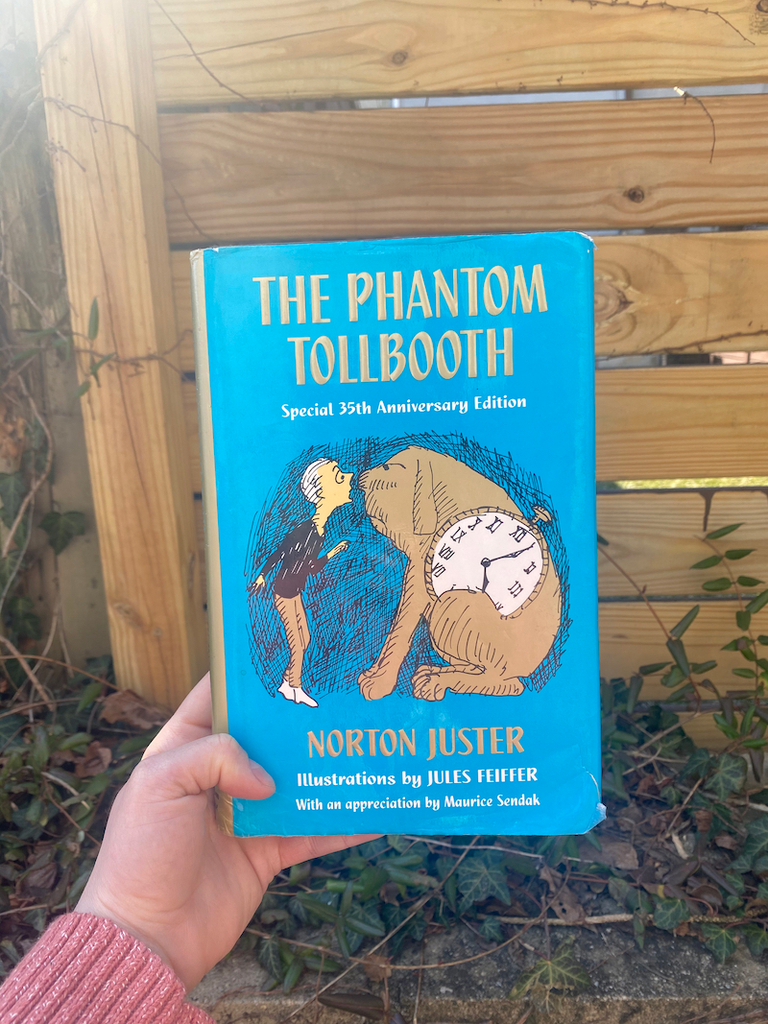

In 1958, Juster started working as an architect in New York City and received a grant from the Ford Foundation to write a book about cities for children. This work got boring for him after a little while, and he was stuck in the Doldrums. He then began to write the story of Milo and his unintentional journey into the Lands Beyond. Jules Feiffer provided illustrations, and The Phantom Tollbooth came to readers in 1961. It went on to be adapted into an live action/animated film and a musical.

Although Tollbooth looms largest in Norton Juster’s body of work, he also started his own architecture firm in Massachusetts and taught architecture and environmental design at Hampshire College from 1972 to 1990. He retired from both the architecture firm and the professorship in the 1990s.

Although not as prolific in his writing because of his architecture and professorial duties, he continued to write and publish books after the success of The Phantom Tollbooth in 1961. He wrote and illustrated The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics in 1963, and it was later adapted into a short film directed by Chuck Jones and Maurice Noble in 1965. It went on to win the Academy Award for Animated Short Film. He also worked on a book called Otter Nonsense with Eric Carle, and later helped design the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Norton Juster united with Jules Feiffer again for the first time since The Phantom Tollbooth on the book The Odious Ogre (2010). It had many of the flairs of wordplay and visual humor that defined Tollbooth, but Juster said it was meant for a slightly older audience. Juster’s last published book was Neville, illustrated by Brian G. Kraus, in 2011.

The Phantom Tollbooth still finds readers to this day, with over five million copies sold. Juster enjoyed the Wizard of Oz book series and read a lot of the Russian and Yiddish books at his family home, so it makes sense that he was influenced to write a portal fantasy book obsessed with wordplay. When Milo (the main character of Tollbooth suffering from boredom) goes through the mysterious tollbooth to the Lands Beyond, he encounters a variety of corporeal illustrations of idioms and common phrases. The Spelling Bee, the Humbug, and Tock (the “watchdog”) go through places such as Digitopolis, the Mountains of Ignorance, and at one point accidentally jump to the island of Conclusions.

In a piece for NPR in 2011, Juster discussed the initial lack of enthusiasm for The Phantom Tollbooth in the 1960s. Apparently, the deeply held belief was that fantasy was “disorienting” for young readers and therefore inappropriate. All children’s books should be simple in terms of story and vocabulary so children wouldn’t get discouraged and leave books behind. In response, Juster wrote, “[My] feeling is that there is no such thing as a difficult word. There are only words you don’t know yet — the kind of liberating words that Milo encounters on his adventure.”

Hand-wringing about what kids should or should not read continues, especially around the issue of queer children’s books. The idea of serving kids challenging books with different stories that may be unfamiliar to them has been a constant debate, but Juster proved with the success of The Phantom Tollbooth that kids were always hungry to explore new worlds. Like Milo, kids actually want to explore things that they may not be familiar with in their reading, whether they’re going for the classics too early or reading books above the arbitrary reading level. The organization We Need Diverse Books also addresses this need for kids to read widely about topics that may seem complicated or heavy.

Even though there are far fewer tollbooths around, I think The Phantom Tollbooth is still the perfect reading experience for kids interested in fantasy and wordplay. When my parents read the book to me as a kid, and when I would go and reread the chapters by myself afterwards, I was fascinated by the literal illustrations of abstract language topics that I didn’t totally understand yet. The Phantom Tollbooth sparked a love of portal fantasy for me, and an interest in how to make regular life a little more interesting and exciting. Juster’s entire body of work pushed us to look right outside of our circles of familiarity and engage with things that seemed odd or confusing. I hope The Phantom Tollbooth can continue to be a way to shepherd young readers into the Lands Beyond and spark their imaginations far outside their bedrooms.