One of my favorite Instagram accounts is Cheap Old Houses—as someone who lives in an older Victorian, seeing the love and passion for older architecture and charm fills me with joy (even if many times it is so hard not to roll my eyes at the comments about ghosts or about “bad neighborhoods”—a coded phrase for not white and gentrified). Periodically, an old library pops up on the account, and it inspires me to dig into that particular library’s story. That was the case with a former Carnegie library in Middletown, Ohio. It is still for sale as of writing, now listed at under $125,000.

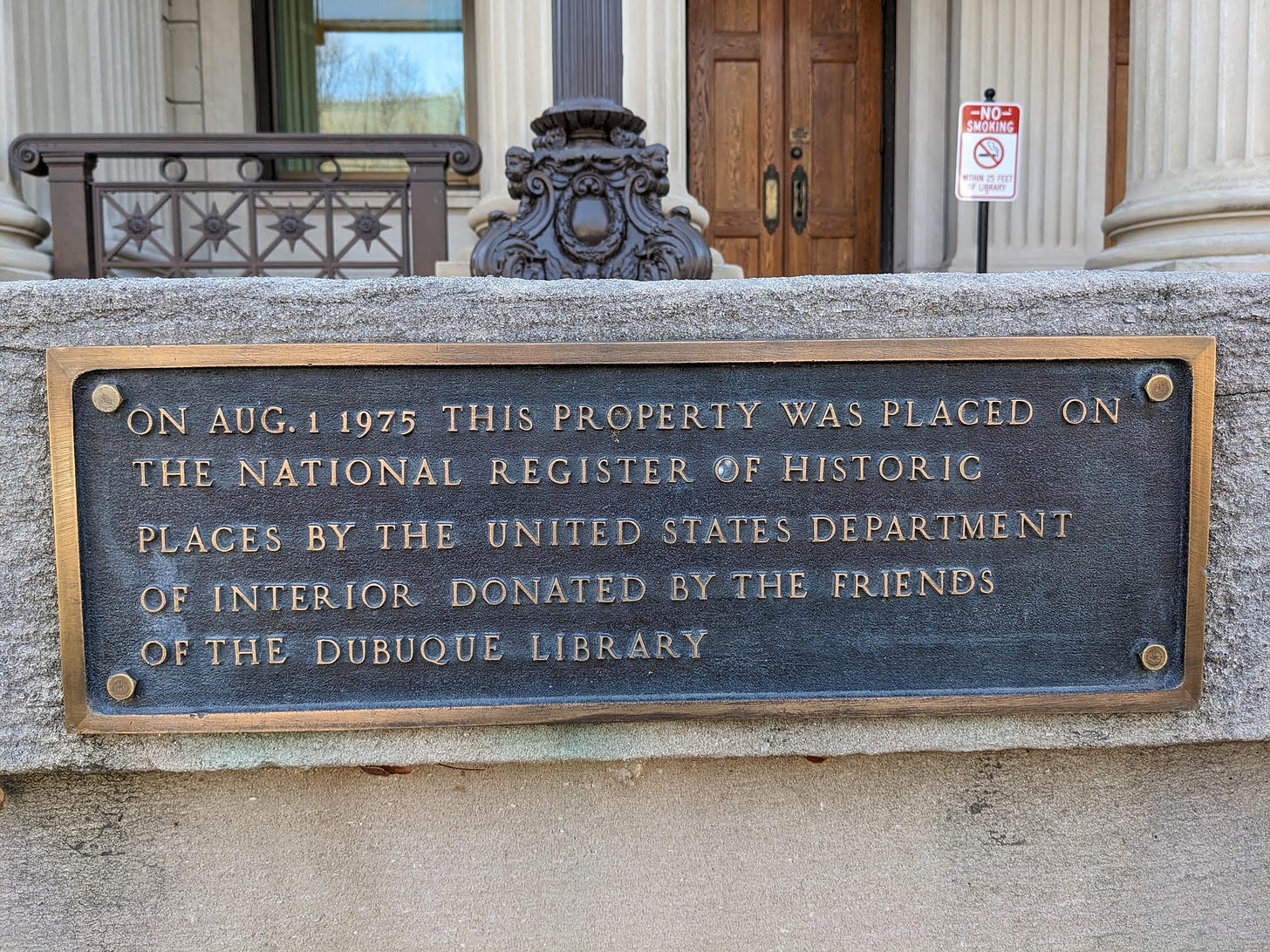

Inevitably, when talking about former libraries for sale, questions that pop up include why anyone would ever sell such a historic landmark. Carnegies are well-known and exemplify a historic belief in the importance of libraries to the people, and so for many, the idea of selling one of those buildings is challenging. Indeed, some Carnegie libraries are landmarks and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but not all of them are. Some of those landmarked libraries bear commemorative plaques while others do not—those are not actually given to institutions granted the status but instead are purchased by the institution itself.

There are 800 Carnegie libraries still in use today as libraries. About 300 have been destroyed, and the remaining have either been repurposed for other public institutions or have become private property. This particular article does not question whether or not these facilities should be saved or deemed historically significant, but instead, wonders whether or not the investment by Carnegie was wise.

That question, as well as the questions about why these buildings aren’t deemed essential landmarks, gets to the heart of how much mythology and misunderstanding there is about these Carnegie libraries.

What are Carnegie libraries, anyway? What historic value do they have and how do those deemed important enough get listed on the National Register—and what benefit is there to being included? Let’s dive into that, plus look at some of the architectural styles you might see in older libraries, both those which are Carnegie and those which are not.

What Is a Carnegie Library?

Although many think that a Carnegie library has a particular architectural style—I know I did!—what Carnegie library means is simply that part of the library’s initial costs were helped by funds from Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie was a 19th-century industrialist and philanthropist. In just 33 years, between 1886 and 1919, he donated $40 million dollars toward the development of 1679 libraries across the US. The free library movement dominated the decades prior to this investment, where reformers across the country saw public libraries as crucial for helping to educate and entertain Americans as the country rapidly industrialized. It would help educate a voting populace—and this is important because public libraries, despite their reputation for and contemporary commitment to inclusivity, were discriminatory for marginalized people—and libraries were seen as alternatives to social activities like drinking and gambling.

The problem, though, was money. US cities and municipalities did not yet have the right to tax their residents. Income tax did not exist until after the Civil War, and other taxes did not emerge until the early 20th century. The upfront costs of building a community library were immense: from the materials to construct the facility to the shelves, desks, and books inside it. Many were staffed by volunteers, including members of local women’s groups who helped get the library going in the first place.

His own experience as a child instilled the power of libraries for Carnegie. He saw libraries as places where people bettered themselves. We know he did, and given how much knowledge helped him succeed, it is likely he saw not only benefit for the individual but for businesses more broadly. Companies want competent workers (and it should be noted that as much as Carnegie wanted people to educate themselves and have access to culture, he was not pro-worker and was aggressively anti-union, especially within his own companies.

Carnegie’s philanthropy toward libraries came in two waves. The first helped fund 14 community centers that incorporated libraries as part of a bigger space; the second was solely for the development of libraries. During this second period is when the bulk of Carnegie institutions were funded, and those who applied for the funding were most likely granted if they were small communities that lacked cultural institutions. This is why you see so many Carnegie libraries in the Midwest: these were towns without much in them for their residents. In segregated communities, separate libraries could be funded to service white patrons in one and Black patrons in another.

Potential libraries needed to apply to get the funds, and they were open to any English-speaking nation (this is why there are Carnegie libraries in South Africa, Barbados, Tasmania, New Zealand, Canada, Belgium, France, and many other countries). Those applications went through Carnegie’s secretary James Bertram, and the applications asked to demonstrate need, a site location, provide public funds for support, ensure that 10% of the cost of building the library was allocated annually to keep it operational, and keep the facility freely available to the public. Carnegie’s early plans included endowments for these institutions, but he believed that if communities were not financially supporting the libraries themselves, the spaces could “become the prey of a clique.” Bertram made the decisions on what communities got access to funding, and the Carnegie funding was only given when proof of the community being able to afford the remaining cost of construction was demonstrated.*

In other words, Carnegie libraries were only partially funded by Carnegie. He also did not make the final decisions on which projects were granted. After 1911, Bertram was no longer involved either. The decisions landed in the hands of the Carnegie Corporation. Not all library applications were approved, either—Bertram or later, the Corporation would determine that the facilities already housing the community library were adequate.

Carnegie had no involvement in determining where in a community the library was built. He and Bertram were also not involved in what the library building would look like. The help they provided in these decisions came down to making sure the library had room to expand in the future; roughly one out of three of the funded facilities experienced controversy over the location of the library.

Library funding from Carnegie stopped just four years before he died. This decision came when a report showed that while these communities had benefited tremendously from libraries, what these communities really needed were people to staff the library—something that the funds were not for.

Common Architectural Styles of Public Libraries

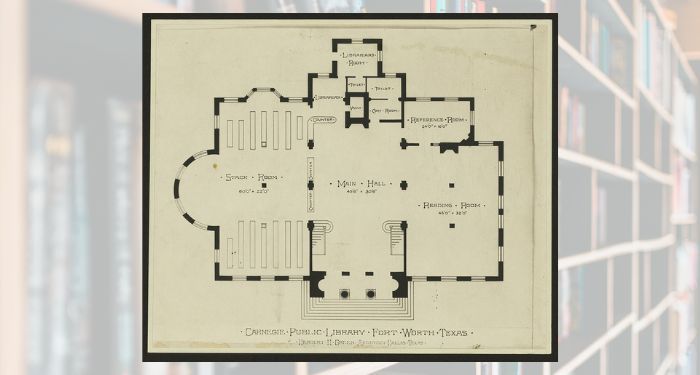

A challenge that came up for many of the recipients of the funding was what their library should look like. Again, Bertram and Carnegie were not in the business of making those decisions. Eventually, though, they did develop a basic guide with the help of library workers that helped in guiding the majority of Carnegie libraries, The pamphlet, “Notes on the Erection of Library Buildings,” includes the following:

- Do not allocate too much space to bathrooms, stairs, or closets;

- A top floor with space for storing books and space for seating both adults and children; this space should be one large room divided by bookshelves or glass dividers with a centrally located desk;

- A basement level with a lecture room, utilities, and conveniences for patrons and staff;

- Windows placed high enough for shelves to flow beneath them, and the suggestion that windows should help light the entire space;

- Avoiding fireplaces, since those took away shelving space;

- The exterior design can match the desires of the community;

- Including Carnegie’s name in the library was not required.

Many of these suggestions were in line with trends being determined by the American Library Association (ALA). ALA recommendations moved facilities away from the high style of early European libraries—alcoves, tall shelves, ladders—and into more accessible styles where sightlines and supervision were better.

In this era of libraries, most were closed stacks. Patrons were not able to freely browse materials but had to request them from a staff member or volunteer. Carnegie helped change that with one of his early libraries. Creating open shelves helped reduce costs, and library workers could oversee the entire facility from their central desk. That, of course, is reflected in the design guides many Carnegie libraries used.

All of this is to say that while there might have been best practices for the library’s style, nothing needed to be uniform until near the end of Bertram’s term—he followed the recommendations more stringently as time went on. But even that was not especially uniform in application.

Because most Carnegie library architectural decisions were made at the community level, some carry slightly more significance than others. Various firms began to market themselves as experts at Carnegie libraries at the local and regional levels. This made a lot of sense: those who sought the funding were not experts, and they were desperate to utilize the funding provided to make the library a reality. You might notice a particular aesthetic within one region of the country but not elsewhere, even if all of those libraries are Carnegie libraries. Patton & Miller of Chicago, for example, did over 100 Carnegies in the Midwest, while William H. Weeks in California did 22.

According to the California Carnegie website, Weeks’s libraries mirrored trends in architecture more broadly:

Three of his earlier commissions, in 1902, 1903, and 1904, were in the Romanesque style, while another, his 1903 design for Watsonville, was an elaborate variation on the triumphal arch theme. From 1906 through 1911 he designed eight Classical Revival Carnegies, of which seven were the temple style, and one Spanish Revival building. Between 1913 and 1921 he built seven Classical Revival libraries, two in the triumphal arch style and five in the more minimalist style, as well as two Craftsman cottage libraries.

Six Weeks libraries are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Peruse the styles of Carnegies and you’ll see a little of everything. Mirror Lake Community Library is in the Beaux-Art Style, while the former Guthrie, Oklahoma, public library was in the Second Renaissance Revival style. That facility is no longer the public library, but instead serves as a local museum following a deal with a local philanthropist not to tear it down when a larger facility was needed. Bayliss Public Library (CA) is in the Classic Revival style, while Las Vegas, New Mexico, has a Georgian Revival inspired by Monticello. Denver, Colorado, began its public library as a Carnegie in the Greek Revival style, and the Braddock, Pennsylvania, Carnegie is in the eclectic medieval style.

In the Midwest where I am, one of the first (maybe the first) American-developed architectural styles is the Prairie School style. That’s the creation of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose student Louis Sullivan helped grow the aesthetic of low roofs, open floor plans, and plenty of natural wood and stone. It became popular at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th, making it a popular style for libraries of the time. You can look through a gallery of some of these Prairie School-style libraries here, and notice especially how many have plenty of space for use both in front and behind the building itself. Sullivan was part of the team behind the Flagg-Rochelle Public Library (IL), and you see not only the Prairie School style here but also the influences from some of the work he did in Chicago.**

How Does a Library Become a Historic Place?

So now that we know what a Carnegie library is and what it is not, let’s talk about something that has popped up a few times. The Flagg-Rochelle Library above is part of the National Register of Historic Places, as are most of the libraries mentioned above.

The National Register of Historic Places is maintained by the National Parks Service. It was created in 1966 in order to create a central registry of buildings, objects, districts, communities, and sites across the country that have historical significance. Listed places represent something important to the heritage of the country, be it on the national level, regional level, or local level. Via state, federal, or tribal historic preservation offices, people or organizations can nominate a place. Review boards in each state evaluate the applications and make recommendations on whether or not it should be listed and where it should be listed—if it’s just at the state level or deserves the honor at the national level.***

But the designation does not necessarily put restrictions on buildings not held by the federal government nor those receiving certain federal funds. In other words, while there might be regulations at the state or local level when it comes to what can or cannot be done to buildings on the National Register, nothing changes for the building with the designation. As mentioned earlier, there is no granting of a plaque either—those are paid for by the owners or patrons of the facilities if they’re desired.

There are benefits to the designation, including access to funds and signaling of commitment to historic preservation, among others. Being listed is pretty damn cool, especially because there are people who plan their travel around visiting places listed on the Register. The database, which is still being digitized, is both downloadable and searchable.

The process is a lot of work.

It also reframes the questions that arise when one of these buildings is either destroyed or sold off: at what point does a building retain historical significance to a community or region? For Carnegie libraries, is it the fact a philanthropist helped fund its initial iteration? Is it the design style of the library and its connection to an architectural movement? It’s hard to say, but what is clear is the same issue that led Carnegie to stop providing funds is the same issue that arises in seeking National Register designation: people power is limited.

Not every community will have a Carnegie library on the list, and that’s okay. Some buildings fall into disrepair because they were not meant to last for centuries. We might hope they would and might like them to, but in a desperate plea for funding a need to prove support to complete an initial public library project, how many corners were ultimately cut in small towns across the country? If money was tight enough to seek a grant, then it was likely no more in abundance to make all of the repairs that would inevitably emerge as time went on. While we know and appreciate the craftsmanship and pride in these community jewels, at some point, their upkeep may just become unsustainable or even downright dangerous.

The good news is that the history of any one building is not lost when the building itself disappears. But the bad news is, it takes people to record, preserve, and share that history.

A quick search for “library” in the current National Register of Historic Places should lend hope, though. Over 1,200 entries emerge. Some are Carnegie libraries. Some are completely different libraries.

Even if we lose a few of the physical Carnegies in the future, not only were they clearly an investment worth making, but they live on in hundreds of places across the country.

Maybe it’ll be you or me who buys the next Cheap Old Carnegie we can and do something with it beyond our wildest dreams as book lovers.

Notes:

* A story that popped up several times about the need for a local dedicated library came from Chatfield, Minnesota. The pre-Carnegie library there ran out of a bathroom and the matron of the bathroom was the “librarian.” The facility was inside a local store.

** My favorite public library in the Prairie School style is the incredible Lake Geneva Public Library in Wisconsin, but this particular library is not a Carnegie. I cannot recommend enough digging into this 1944 history of the library—the descriptions of the people who made it happen are incredible.

*** Here’s information on how to get the application process started.

Find more posts like this via our subscription publication, The Deep Dive! Weekly staff-written articles are available free of charge, or you can sign up for a paid subscription to get additional content and access to community features.