In fall 2023, Annabelle was sitting in a classroom with windows that faced the school cafeteria. From there, she witnessed an altercation between a teacher and her school librarian. Annabelle described it as unlike any interaction she’d seen between school faculty members. It was loud, it was hostile, there was a lot of gesticulation, and it grabbed her attention.

The argument was over books. Specifically, this argument was over The Handmaid’s Tale (Graphic Novel), which Annabelle discovered after her class period ended and she went to the library to ask. The library and the librarian were among her favorite things at school.

That moment catalyzed her. Annabelle knew she had to ensure that the classic turned graphic novel would remain on shelves in her school’s library. But she learned quickly that it wasn’t only The Handmaid’s Tale (Graphic Novel) the district intended to ban. There was a whole list of books slated to be pulled from the libraries.

“Myself and a lot of other students in my school were very concerned. So we banded together,” she said.

Annabelle’s school—which has a little over 200 students—was small enough to make the word spread easily. Concerned students sprung into action, beginning with creating an Instagram account to spread awareness of the books being removed, as well as a petition. They reached out to district administration, sending letters and asking to be involved in the conversations around the books in their own school library.

The students wanted to find a compromise between keeping the books on the shelf as-is and the plans to remove them entirely. While they were initially met with positive reception by their school’s principal, who was open to considering alternatives (such as creating opt-in/opt-out forms for certain titles or limiting titles to specific grade levels), the tenor changed as the conversations went up the administrative chain.

“The district came in and said there was no alternate solution. They were taking the books,” said Annabelle. “They didn’t want to continue the conversations and they kind of prevented our principal from even discussing it further with us.”

“Students came with compromise and we were met with being completely denied any involvement in it and no place in the conversation. No matter how upset we were and no matter how respectful we were and no matter how many right avenues we took to do this, they continued to ignore us and shut us out.”

The West Ada School District began removing books from schools during the 2021-2022 school year, around the time book banning began to heat up nationwide. Among the titles removed that year were Gender Queer and This Book Is Gay, though several other LGBTQ+-focused titles were challenged. These book challenges and removals happened alongside the banning of 24 titles in the neighboring Nampa Public Schools. (It should be noted this district did not start banning books during this current wave of bans, but their speed picked up in the current fervor—a piece from the National Coalition Against Censorship shows how the district was working to eliminate “inappropriate” books in 2014).

Early into the 2023-2024 school year, West Ada School District’s Library Coordinator emailed all of the librarians and principals a list of 44 titles deemed “inappropriate,” per reviews on Moms For Liberty’s BookLooks website. One week later, a committee met to discuss the books—which included The Handmaid’s Tale Graphic Novel—and elected to remove 10 of the books from all schools in the district. The meeting happened outside the normal review committee process and did not include the input of any district librarians nor educators—save for a single secondary English teacher.

There was also no student input at all.

In addition to banning The Handmaid’s Tale Graphic Novel, pulled for its visual depictions of nudity and sexual assault (key themes in the dystopian story), the committee banned Gregory Maguire’s Wicked, Water for Elephants by Sarah Gruen, Jaycee Dugard’s A Stolen Life, and other popular banned titles. The time between the call to review the books and remove them was less than a week, and the team of administrators and one educator relied on and justified their decisions from the Moms For Liberty BookLooks reviews. That’s in the district’s prepared statement.

Another outcome of the book bans, per Annabelle, was the decision by her school’s librarian to retire. Not only was she the target of verbal ire from a staff member, as Annabelle witnessed, but the librarian’s input was never sought when it came to banning books in the collection.

“She built that library from two cardboard boxes to a beautiful, thriving space,” said Annabelle, who found solace in the library throughout her time in high school. “[The librarian] was so wonderful, so welcoming, and so informative. She wanted to continue to do her job but could not bear to continue working in the environment that the district was creating.”

Book banning was not Annabelle’s, nor her classmates’, first or only concern related to her school’s library. During a student council meeting, Annabelle recalled the superintendent being surprised that students did not want their library to go all digital.

“Every single person in that student council meeting was extremely against that. Discounting how important libraries are as physical spaces and refuges is so detrimental. He did not see the appeal of physical libraries at all. That shocked me to my core.”

Between the book banning and the lack of concern that administration showed for its students, Annabelle felt not only defeated but disgusted. She also felt lucky: she would be graduating, so the issues would no longer impact her day to day life. That wouldn’t be the case for her classmates, including those who had been fighting to ensure those books remained in the school libraries.

That’s when she realized she had no interest in shaking her superintendent’s hand at graduation. He wasn’t there to celebrate her nor her efforts. He’d shut her and her classmates down instead of engaging in negotiation. When she took the paths she was told to take to enact change, Annabelle and her peers were cut off before even being given the opportunity to give their perspectives as those who would feel the direct impact of banning books in the district.

Annabelle started to think about what she could do instead of shaking Dr. Bub’s hand. When she had an idea, she approached her parents first, who were immediately supportive.

“My parents have always said you can watch and read whatever you want but we want to be involved in helping you process and analyze it,” she said, explaining that in fourth grade, she really wanted to read The Giver. “My parents prepped me for that one since it was heavy and maybe not really for my age groups. That’s one of my favorite books now, so it worked out well.”

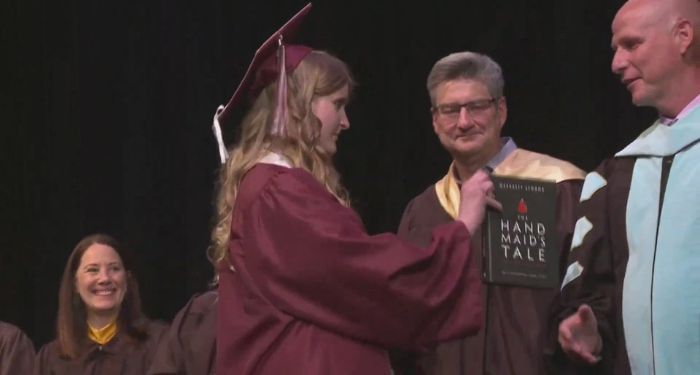

As Annabelle prepared for graduation, she kept her plans to hand Dr. Bub a copy of the now-banned The Handmaid’s Tale Graphic Novel to herself, her parents, and her best friend. This wasn’t about creating a scene nor about making herself the center of attention, two things the straight-A student emphasizes she does not like.

Annabelle elected to hand her superintendent a copy of the book because she was so frustrated after a year of fighting against book bans. Despite going through all of the appropriate avenues to fight the ban, her voice—and the voices of other students in her school and across the district—continued to be ignored. She did not want to shake Dr. Bub’s hand during the ceremony because he had not been an educational ally for her.

“Handing him the book was the way I could get the last word in,” said Annabelle, “I already felt so powerless.”

Upon being handed the book, which Annabelle kept tucked in her graduation gown sleeve for several hours, the superintendent let it fall to the stage floor.

“I was shocked. I expected him to have a little more decorum. I think if he had taken it and set it off to the side, then this would not be the spectacle that it is,” she said. She left the book on the floor in front of him as he crossed his arms not accepting it, then she proceeded to walk through a line of teachers waiting to congratulate her on her big day.

As Annabelle continued, she saw her school librarian there, who was crying. The two of them exchanged a big hug, and then Annabelle saw her senior English teacher.

“She’s been a big mentor for me and helped me through a lot of my early activism as I tried to get the message out there. She didn’t know about what I was going to do on stage, but I don’t think she was surprised.”

Seeing both her school librarian and English teacher there as she exited the stage led Annabelle to begin crying about that moment—in a good way. She felt supported, she felt seen, and, for the first time in her nearly year-long battle over books being pulled from her school library, she felt heard.

It wasn’t just the supportive adults in the room cheering her on. So, too, were her classmates. People ran up to her, hugged her, and gave her fist bumps.

“A lot of my senior class was very happy, as were the underclassmen that were at graduation,” she explained. “I hope that it not only generates conversation around the issue but I also hope that it can be comfort to other students.”

Even if handing him the banned book was not intended to make a splash, it did. And more, it solidified for both Annabelle and her classmates that the fight is far from over and that continuing to speak up and out in ways that allow you to be heard is crucial.

Seeing her school librarian and favorite English teacher as she walked the line of teachers may have made her really understand the power of those adults in her life, as well as the meaning behind her act. But there was something else that struck her as she took in those handshakes from her educators.

“While I was going down the line, the teacher I saw fight with our school librarian that day told me ‘You’re very brave.’ That was an awkward one to get through.”

A lifelong library lover, Annabelle talked about the power of not only her school library but also her public library. Her parents took her to infant story times, and as she got older, she began volunteering there as well. She believes the library helped raise her to be who she is.

She recalled a story from when she was in her middle school years when she was volunteering. The library director decided to cut the budget used for security cameras at the facility. Even though the library was across from a school and had teens “loitering” outside, that cut was made to do something better: create a dedicated teen space. Now there was a safe place for those same “loitering” teens to be after school. It was where those kids could exist and be themselves without being judged or deemed trouble.

“The value that libraries have is layered. There’s the layer everyone thinks of which is education and exploration and escapism if you want it, but then there’s the part where there’s skill building. There’s solace in libraries,” she said, emphasizing that bills like the one in her own state, HB 710, are destroying one of the most inclusive and powerful spaces available to all people.

Annabelle will be attending the Honors College at Portland State University this coming fall. She will be studying English, with the goal of one day going into library science.

The field could not be more ready for champions, advocates, and impassioned library lovers like her.