Running her fingers over her scan for the first time, Karen Trippass could feel straight away that her unborn baby had her husband’s nose.

Born with bilateral coloboma, a rare condition also known as cat-eye syndrome, she never thought she would experience this pregnancy milestone in the same way that sighted expectant mums do, the excitement of seeing the shifting black and white shapes of a growing embryo appearing on screen for the first time.

It was something she missed out on while pregnant with her eldest daughter, Phoebe, 10 years ago. Questioned by medical staff and social workers on her ability to care for a newborn at that time, Karen says being visually impaired meant she was treated differently and she suffered from depression, finding it difficult to bond with her baby before her birth.

This time round, she was able to “meet” her baby through her 29-week ultrasound thanks to technology that creates a raised image, providing a tactile feel of her child wriggling in her womb. She says having this, and also being able to hear the heartbeat, helped her feel more connected.

Karen’s second daughter, Ruby, is now eight weeks old, and her scan hangs up at their home in Surrey.

“The first thing I remember noticing was her nose,” she says. “She’s got my husband’s nose. I could feel the top of her head, her nose, the dip of her eyes… I’ll always treasure it.

“Both my babies are IVF, it took us a long time to get there. So the whole thing’s emotional anyway, but then getting to see your baby like everybody else does… I just hope that every visually impaired woman who has a baby could get that opportunity.

“I don’t expect the NHS to be rolling it out, but even if you had to pay a minimal charge, I think a lot of people would prefer it. I just think it’s amazing, the concept of having family pictures from now on would be pretty cool.”

According to the NHS, there are more than two million people living with sight loss in the UK, with around 340,000 registered as blind or partially sighted.

Karen’s scan of Ruby was created by camera firm Canon, and is being featured as part of its new World Unseen exhibition, launched in partnership with the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) – “the photography exhibition you don’t need to see”.

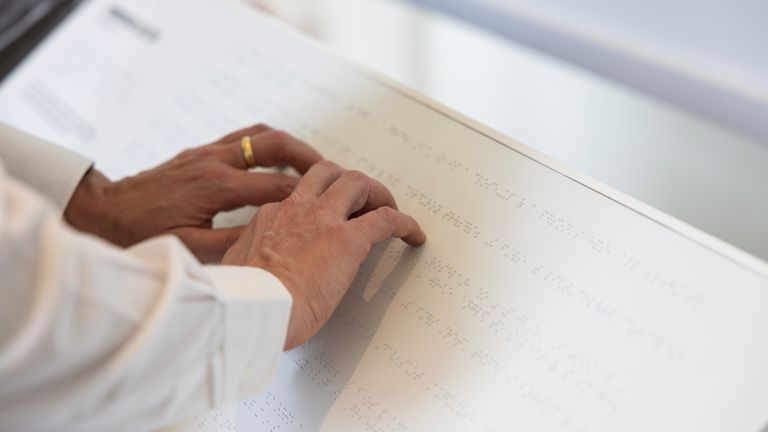

Designed completely with the experience of blind and partially sighted people in mind, the exhibition features a series of pictures taken by world-renowned photographers, some who are visually impaired, accompanied with elevated prints, audio descriptions, soundscapes and braille.

For sighted people, traditional images are obscured in different ways to convey different types of visual impairment, from glaucoma to diabetic retinopathy. It is an insight into the difficulties faced by blind and partially sighted people, a challenge to see life through their lens, and a reminder of the vision those of us with sight rely on and take for granted every day.

At the launch event, even the canapes play with your senses – we are encouraged to put on headphones playing sounds of the sea, a scent spray filling the air with salt and vinegar, as fish and chip nibbles are presented.

Among the photographers whose work is featured is Ian Treherne, from Essex, who is known as the Blind Photographer. Born with the condition RP Type 2 Usher Syndrome, he has been deaf since birth and over the years has lost almost 95% of his sight.

“I hid my blindness for years,” he says. “I acted as a sighted person for a very long time. When I was growing up, disability was a very, awkward, difficult topic. Only my close friends knew about it. Then in my 30s, I sort of ‘came out’ as a blind person and it’s done me the world of good to be open and honest about it. And I think by doing photography and working alongside other people with disabilities, you can really improve the bigger picture among the general public.”

Ian says he has always been creative and photography allowed him to capture moments in time as he was losing his sight. But there was also a rebelliousness behind his desire to get behind the camera.

“I knew that doing photography and being blind was going to hurt some minds, hurt some brains,” he says. “I knew it would raise some questions.”

So he taught himself, practising with his camera and researching on the internet. “With the condition I’ve got, I have to work probably 10, 20 times harder than a fully sighted person,” he says.

“It’s all a learning curve. I think that’s really the biggest boundary in society, it’s changing the mindsets, or adjusting the mindsets. I think people are sometimes just afraid to ask the question.”

The World Unseen exhibition feature works from world-renowned photographers and Canon ambassadors from around the globe, including Brazilian photojournalist Sebastião Salgado, Nigerian photojournalist Yagazie Emezi, sports photographer Samo Vidic, fashion photographer Heidi Rondak, and Pulitzer-winning photojournalist Muhammed Muheisen.

A photograph from Kenya of the last male northern white rhino, taken by award-winning South African photojournalist Brent Stirton, also features. You can feel the roughness, every groove of the animal’s skin, as you run your fingers over the elevated image.

Photographs of Lioness Chloe Kelly’s decisive goal in the Euro 2022 final at Wembley, by Marc Aspland, are also on display, with an audio description reliving the moment of the win.

But Ruby, of course, is the star of the show, cradled by her mum in front of her scan. “It’s funny to think of people feeling Ruby’s picture but I love the idea that quite a lot of visually impaired people will feel what a scan picture is like, because I didn’t know what to expect,” Karen says.

“To have this memory, this opportunity to ‘see’ – I say see, or feel – my baby before she was born was awesome. And to have a record of it and get to show Ruby when she’s older, it’s so special.”

The World Unseen exhibition has opened at Somerset House, in central London, and runs over the weekend